Read the first part of Maize's articles on Wayward Strand's voiceover pipeline here.

Pro Tools

We designed our Pro Tools sessions around a balance of streamline recording, and a navigable informative session for editing.

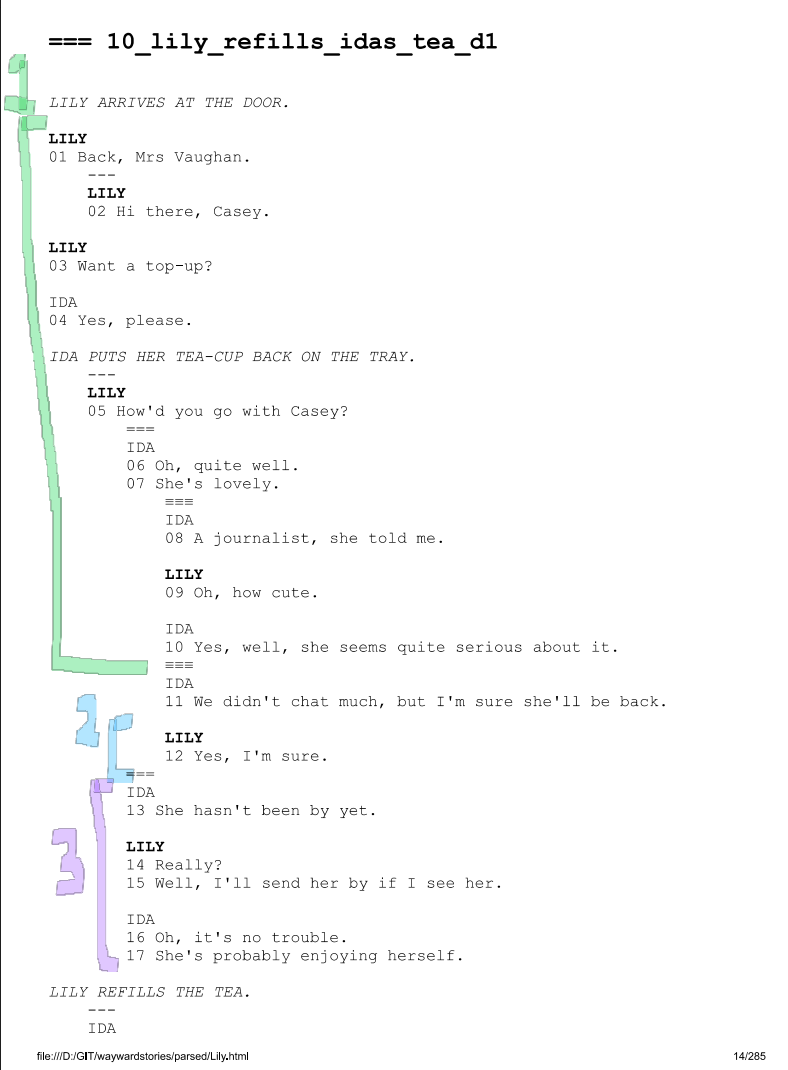

Script numbers align to marker numbers in the tsv file exported from our scripts, which goes into Pro Tools. This ensures everyone is using the same numbered references. This was inspired by how conductors work with musical scores. While everyone is looking at a different score, we all use the same bar numbers. It proved easy for the actors to align with. Considering their scripts were non-linear, the numbers were a good anchor. It also meant that the engineer could skip around to whatever line we were recording from, and record or playback from there.

These numbers are also used to name the .wav files, and import them into the Unity project, where along with their folder names, would hook into the scenes.

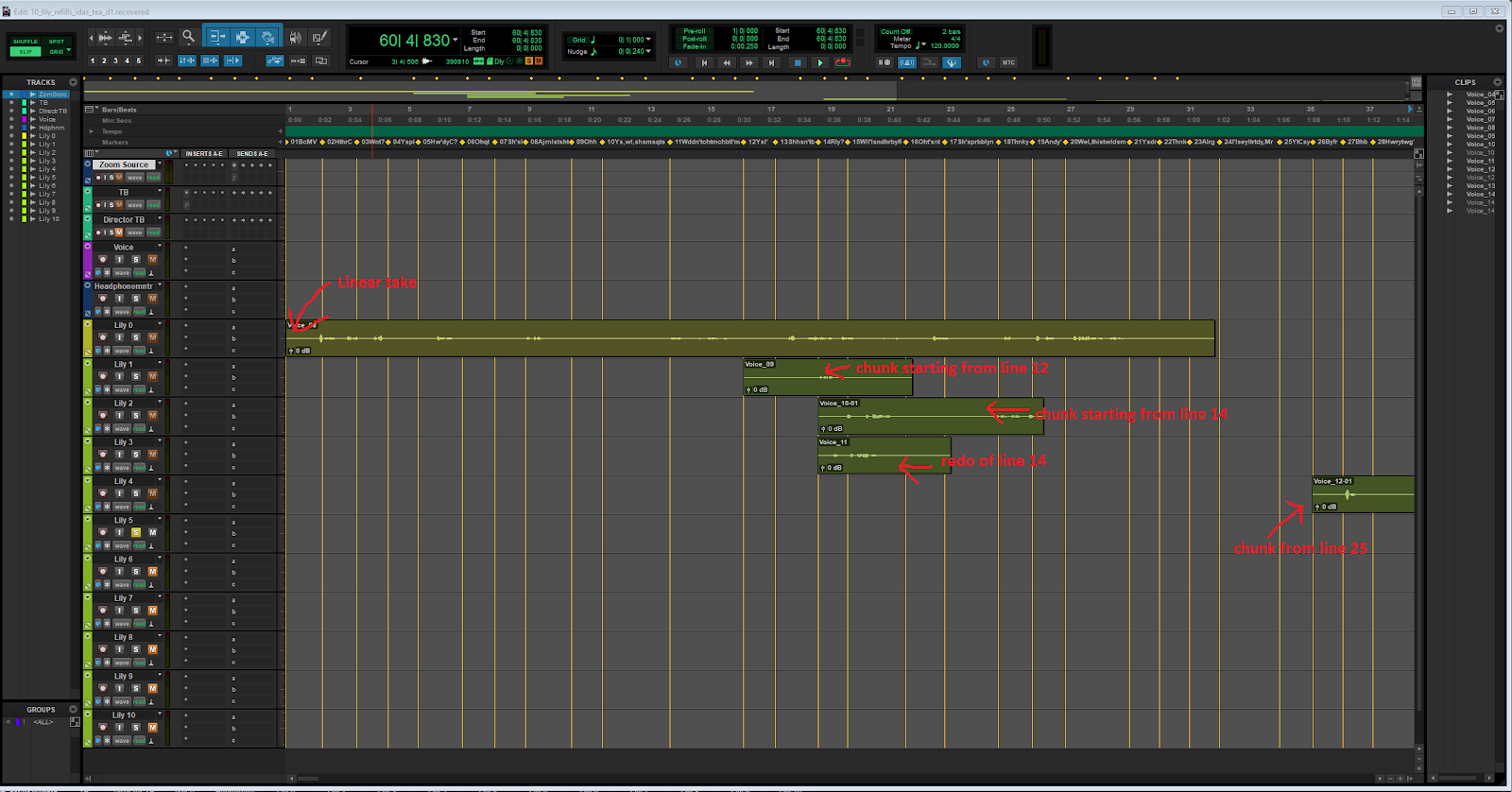

Here’s an image I supplied to studios for them to understand our pipeline.

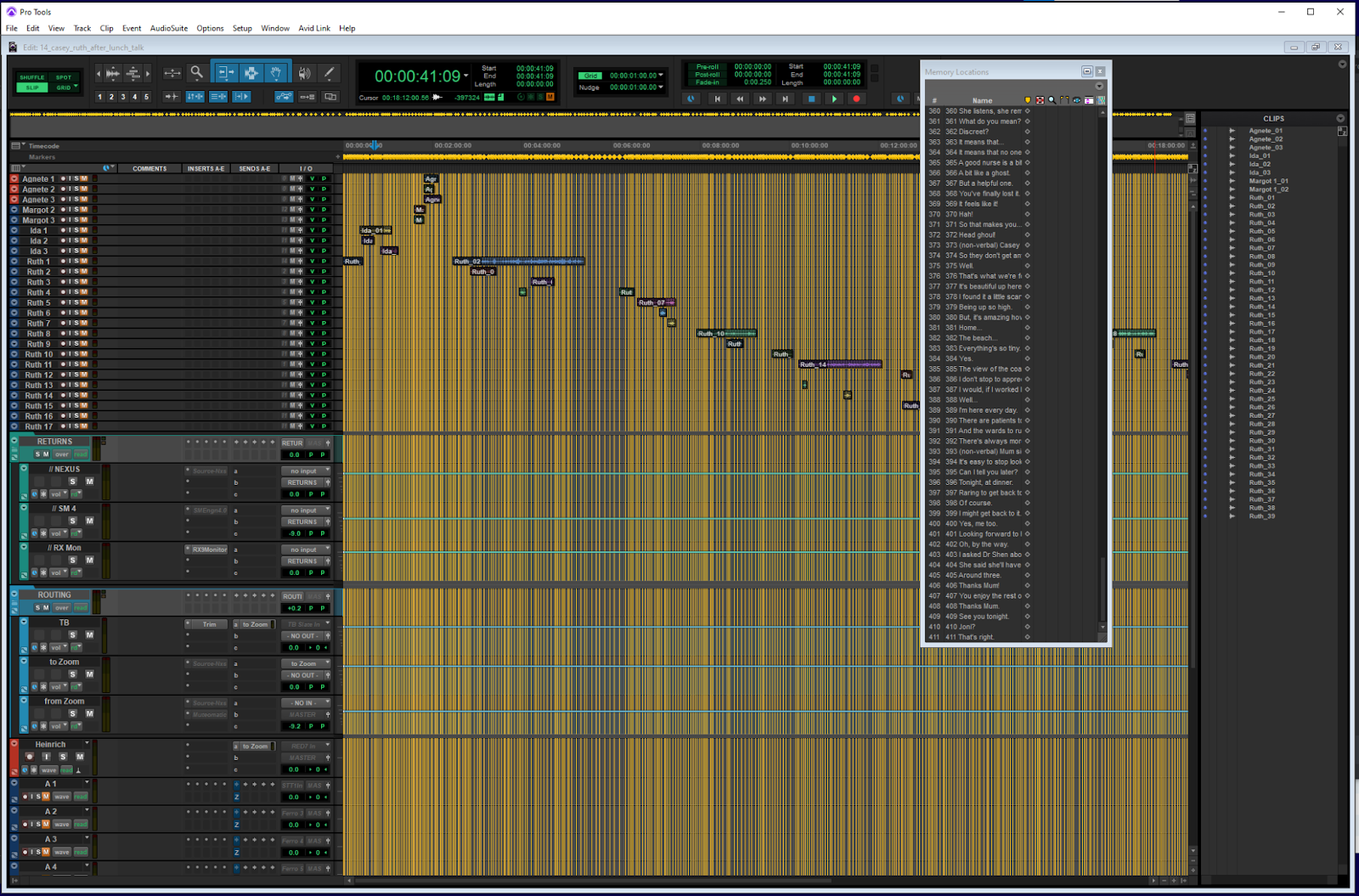

I also attached this one. Not to freak them out, but to emphasise how important it was that we stick with our designed process, across the many thousands of lines of dialogue.

It actually turned out that the 500 marker projects, while intimidating, became the most streamlined to record and edit in!

We had to limit project files to 500 markers for two reasons:

- maximum amount of marker that EdiMarker would deal with exporting a Pro Tools data file from was 999.

- maximum number of tracks in Pro Tools was 768. Considering the possibility of one line per track, we didn’t want to push this limit. Or our computers’ limits!

Numbers Numbers Numbers:

When we are recording, we are using three main assets:

- The actor’s scripts

- The marked up Pro Tools sessions

- The google sheets notation files

All three of these have the same numbers appended to the same lines of dialogue. Everyone in the session, actors, engineers, directors all know what lines we are up to.

Maize, Tfer, and Allison defined closely what recording processes would look like. With technical support from Jason, and production support from Georgia.

Tfer is an awesome ADR specialist, working mostly in film. Maize and Tfer had worked together on the previous round of Wayward Strand voiceover for our demo, and previous to that had worked together on another Australian game where Maize played a technical audio role, implementing Tfer’s sound design. So we were psyched to continue our working relationship, and iterate on our processes.

This time, Tfer got us working in Pro Tools, and using a tool called EdiMarker, which she explained would take a text file and create markers in Pro Tools, making it easier to navigate.

Our original plan was to have the Pro Tools markers telling us exactly where the lines started and finished. In our dress rehearsals of the recording process, Allison and I found that this was not possible to maintain, seeing as their timing was actually arbitrary. The timing should be defined by the actors, not the magic number we came up with for speech bubbles to stay on screen in the game. So, they were used to tell us where we started recording that line from. Not quite the same information, but still a massive step toward a more navigable project.

So, if we can not use the marker as the sole source of what recording we are using, we thought maybe we can use tracks! Coming back to Tfer with this new iteration, she recommended that we use clip numbers instead. While you can move things from track to track, they won’t remain a source of truth. But, clip names will remain the same, and Pro Tools will even hold an amount of history of the clip names, as you cut them up. So what we landed on was: the track names being of the characters, and then each clip recorded on that track would be consecutively numbered. So, we can refer to “clip Lily 10”.

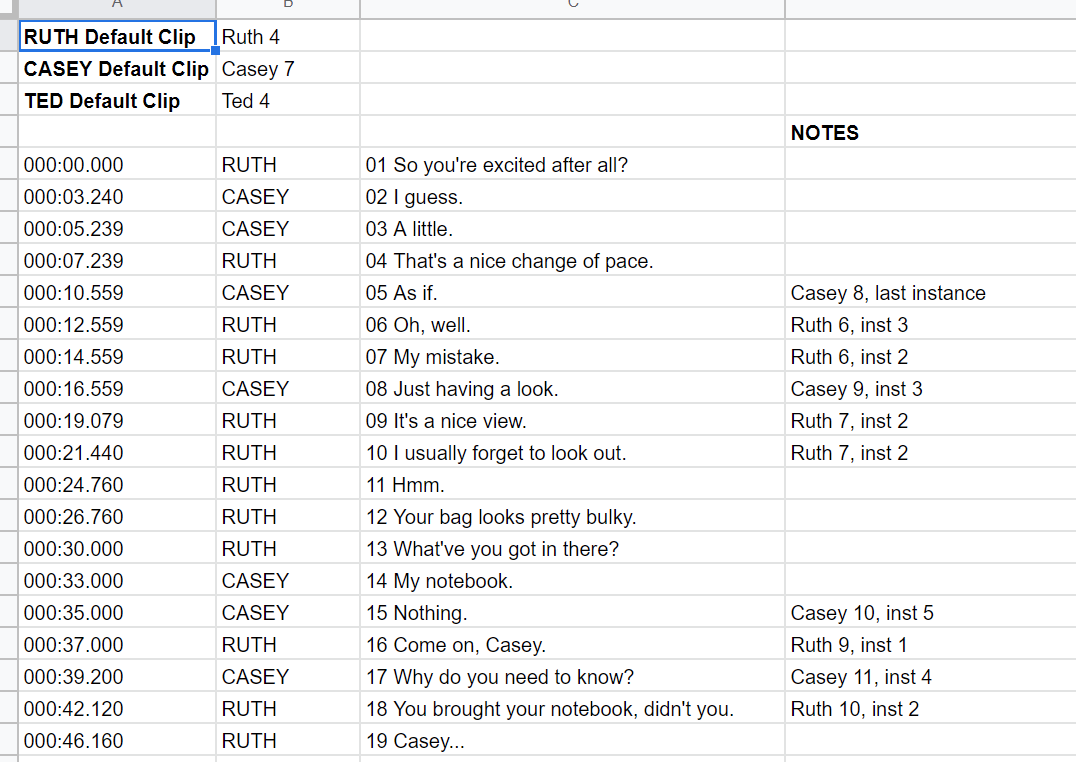

The video that was sent to studios

Jason, who was on notation, was able to quickly note what clip number would be the default take, and then what clip + instance any preferred retakes were, as well as what needed to be retaken, while we were recording.

In our recording session, we would say “rolling clip number x”, and in the notation, we will note what clip the preferred take for each line is on. At the top of the file for each scene, we would write the “default clip number”, where most of the preferred takes will be on, and then write next to the lines, if the take is on a different clip.

We also use the word “instance” for if the line was done more than once on the same clip. Actors would often loop a line, and we would count each instance of it, and then write down the preferred one. The notation could say “clip 11, instance 4” for example.

These notation files would become our “source of truth”.

Tfer and her assistant Kyra can note on the google sheet if this notation seems incorrect, or if the take has a fault in it, and another needs to be chosen. When a comment is left on the google sheet, Jason and I would both get a ping, and one of us would be able to resolve the issue.

We could also use this sheet to split or combine lines. This is where the sheets being the “source of truth” really played in, because the Pro Tools marker numbers would then be incorrect. More on that later!

Editing:

As we recorded characters one by one (we kept to one actor at a time, to limit potential covid spread), we began to drip through samples to Tfer. Tfer was now able to combine her knowledge of the characteristics of our studios, with the character of each actor’s voice. Tfer was able to send through demo edits for feedback. They were all of course excellent, and we had little to no feedback. Being so intimate with our processes and goals, we were able to be on the same wavelength easily.

We knew there would be a team of editors. So Tfer worked fast and created two sets of presets:

Pro Tools track presets using FabFilter EQ, compression, and limiter for each character, and RX vocal cleaning module chains for each character. Some actors played their characters really breathy, some were loud and shouty, some were small and had very pure voices, while others were round and large.

Our editing roles ended up as follow:

Kyra Bellamy and Allison Walker on “slicing”

- Slice up each line in the Pro Tools sessions, into separate clips

- Arrange them on to the “go” tracks for each actor

Tfer Newsome would do final edit

- Tfer would take these sliced-up project files and check through them

- Then implement the Pro Tools track presets

- Bulk edit each clip through RX

- Arrange the clips on to one track, and bulk export named with their line numbers

Maize Wallin anything weird or complicated

- There were scenes entirely in Danish

- There were scenes where we did two completely different versions, to see which we’d like better

- Scenes with extra audio effects on them

- Scenes that took some amount of extra work for one reason or another

Kyra’s contribution was amazing. She had such intense muscle memory of Pro Tools slicing shortcuts, that she would regularly top her high scores of how many lines or scenes were sliced per minute or hour. 800 lines an hour? 1000 lines an hour??

We had a few extra tools that started to read our spreadsheets. Scenes marked as sliced, edited, implemented, tested… How many lines in total in the game, how many more to implement. We watched all our progress bars fill up faster and faster, until they were done! Beers and wine on the Zoom call ensued. Then it was just…

In the third and last part of this series, Maize dives into playing the wavs through Wwise & VO bugs! You can read that article here.

Comments